ALTE #13: DISGUISE

MORE MASKS! MORE UNCOMFORTABLE TRUTHS!

Helen Engelhardt

No more masks! No more mythologies!

“Orpheus,” Muriel Rukeyser

1

When actors first emerged

in the shadow of the Acropolis

wearing masks, people in the amphitheater fainted

believing the very gods had descended from the skies.

2

Song sings in chambers of bone in mouth and nose

chest and head. Do not ignore the pharyngeal regions.

Its day job helps the throat to swallow — (working for the digestive system).

When it joins the vocal cords and resonates — ah, that is singing through the mask!

3

The women tented in black glide through my neighborhood

pushing baby carriages. Their eyes once avoided my eyes. My eyes once looked on them with pity.

No longer.

Now we share the mask.

4

Hiding ourselves from ourselves

I wear a mask for you

I breathe in my own hot wet breath

for your sake and you will

keep your distance

as instructed

for the sake of the living.

DISGUISE

Esther Cohen

When I moved into this building nearly 50 years ago, before the word gentrification was part of many sentences, the building’s lobby looked like a shady subway stop. Now it is painted the red of a Brazilian whore house. The red wasa step up from the greyish grey before. I had an unexpected neighbor amidst the many subsistence artists who worked on occasion, as well as Mr. Gould, the Jamaican pot dealer, Eric the bondage aficionado, and Dora who sang with Philip Glass.

Mrs. Israel wore navy suits and the rest of us would talk about those suits for many years. She walked with a sense of purpose, had a secretarial job in the mid-30’s, and did not, to the best of my knowledge, ever reveal any of the details of her life to a single soul.

She had no visitors. We saw her leaving in the mornings for work returning no later than six each night, doing laundry every Saturday morning with actual curlers in her hair. I lived next door to her for years and she never said much more than hello. On rare occasions, she would comment on the weather.

One day after fifteen years or so she left a note under my door, inviting me for Saturday tea at 3 PM. I was curious about her apartment, and about the unlikely invitation. She was neat and formal, wearing her navy suit. She served us tea in china tea cups, and had a plate of four Oreo cookies. “I thought someone in this building should know this,” she said, after about two minutes of pleasantries. “There was never a Mr. Israel. I call myself Mrs. Israel because it makes it seem as though I was married once. Please wait until I die before you tell anyone else in the building,” she asked. I obeyed her request.

“Disguise” Susan Griss

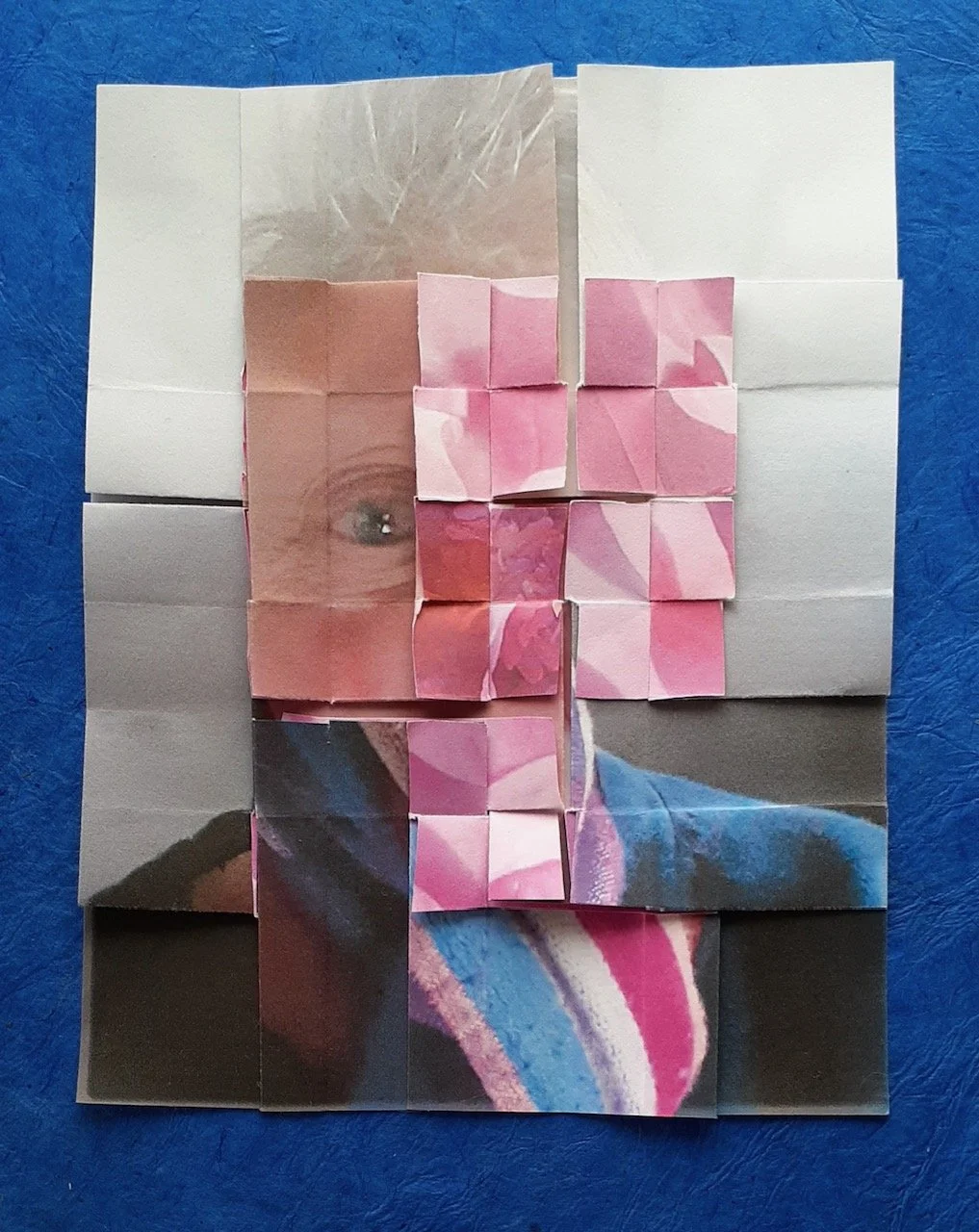

THE BACK OF MY HAND (DISGUISED AS A MOBILE)

Elena Harap

These latter years, I’ve been sterotyping my hands — fingers angling oddly, knuckles bony, brown spots on the skin — in short, the hands one expects of an old white lady. All the stereotypes seem to suggest ugliness, or at best, deterioration. My hands do what I ask of them, so I haven’t considered the subtleties of their character, their beauty, if any. I’ve simply taken them for granted. Homely, practical, hardly a work of art.

I don’t know the back of my hand like the back of my hand. Let me look. Left hand holds the pen. Right hand and I are about to get acquainted, and while we’re at it, right forearm claims attention.

I need to look with new eyes at my skin. My arm reminds me of ridges in sand at the ocean — how the surface responds to waves breaking over it, making parallel lines, humps, valleys, drifts. Here, the energy of my body shapes the inner action of my hand and arm in the element of air. Left hand writes, right hand steadies the notebook. Wrinkles resemble very delicate bangles at the wrist. Maybe you could say these are the friendship bracelets of aging. I turn my arm and suddenly the wrinkles wrap from wrist to elbow like evenly wound threads of faded pale brown silk or fine, almost invisible, wire.

The design of the back of my hand is complex, a pattern of veins and skeletal shapes covered by diagonal lines. Remarkable translucence of the skin, my skin of decades. But skin constantly sloughs off and renews itself, apparently restoring and re-wrinkling.

Switching to my face as a momentary distraction, I imagine using a mirror and exploring how my face plays on changes like a jazz musician. Or I might survey the folds, hummocks, smoothness and texture of my torso. For now, the back of my right hand is sufficient. When I lift the hand for a minute or so, the veins go undercover and I see sculpted branches, a tree with bony limbs and a wind that blows all the wrinkles sideways. A frozen moment of action. I lower it and flex into a loose fist; the wind disappears. The knuckles become smooth, but between them I think I see runes, messages, faintly etched. Much more to interpret here, but in an unknown language.

My hand is the framework for a mobile. My fingers possess a tremor. Suspending the hand and arm a few inches above my notebook the fingers dangle and move. I can see daylight between each one. They’re jointed like bamboo sticks, the color is what E. M. Forster calls “pinko-grey.” The knuckles look like squashed hats. As I move them around my writing room, they seem like trembling bars at a window, defining orange and blue curtains; paintings in various colors of the spectrum; photographs in black and white; sunshine on snow, with its faint blue highlights. The thumb does its own thing, extending at an angle with no motion.

I don’t yet know the back of my hand like the back of my hand, but I begin to understand its ever-changing-ness. Every time I look, a new wrinkle. A masterpiece of a mobile in disguise. The back of my hand glows like a living sculpture on an armature of bone; a relief map with mountains, rivers, and plains; or suddenly, a bird with feathers, about to take flight.

THE AROMA OF QUEENS

Ellen Gruber Garvey

When I was a child in the misery of a Queens tract house development, my mother seemed to have two personalities. Her day-to-day one, wearing a loose housedress or old skirt and blouse, cooking potroast, airing the beds, drinking coffee, screaming. Talking on the phone on the stand in the kitchen, arguing with the other mothers of the block, calling her aunts in the Bronx, yelling at her cousins in Brooklyn and listening to their boasts about their kids. She picked up remembered fights, slapping the back of one hand against the other palm for emphasis. Ground her cigarettes out on dirty plates or the bottoms of coffee cups. She despaired at the endless work of motherhood, we kids who didn’t listen, who threw tantrums, who resisted producing nuggets of our accomplishments she wanted so she could offer them proudly to the neighborhood and family talk circuits.

When she went out for the evening, into the city or maybe even to a party at the progressive neighbors she’d discovered a few blocks away, she was airlifted into another personality. She put on her girdle and svelte dress, straightened the seams on her nylons, stepped into heels, put on a silver necklace made by a jeweler in the Village, and spoke in warm, quieter tones. She glowed with anticipation of a play or a concert. Perfume cemented the transformation from Yelling Mommy to Going Out Mommy.

I know the name of the perfume only because she gave me a pretty glass bottle with one drop of Chanel No. 5 left in it, when my father bought her the gift of a new bottle. I treasured it in a clothing drawer, hidden under socks, to open and breathe in that scent of mommy’s other self. Her jewelry box smelled of it too, another reason to explore it, as did her purse where it mingled with the metallic smell of keys and the omnipresent packet of Kents. I’ve read that Coco Chanel designed her perfume to blend with the smell of cigarette smoke, but everything in those days of omnipresent smokers had to mingle with that choking stench. By itself, the unstoppered bottle smelled of glamour, of the possibility of transformation, of sophisticated adulthood untrammeled by housedresses and children.

Perfume was expensive, not something to wear with a housedress, not even the pretty quilted one with rhinestone buttons. The bottle in my drawer was a caress, like earplugs against the screaming.

INTRODUCTION

Jessica de Koninck

If I have one name in English

and one in Yiddish,

If one is the name

of my grandmother’s mother

and one my grandfather’s mother

If my father changed

his last name from the name

of his fathers,

If I keep my father’s name,

if I take my husband’s name,

When I look in the mirror,

When you look at me,

Who am I?

WHO IS HE

Rachel Berghash

He emerged as a concept from Abulafia, an ancient

Kabbalist, who thought we could be prophets.

He emerged as a stooped man in my synagogue,

a very old man whose voice rang with vigor like a lad’s.

And he emerged again in my dream, an old man

dressed with layers of white cloth, fumbling

through them to find and present me with his might

that lurked beneath, as a prophet would when he

puts his ear to his daemon and strives to be intimate

with the voice inside him. Perhaps I am that old man,

putting down my head during the morning prayers,

attempting to break open the covering of my soul

to release a spark hidden there since the beginning

of time, when it began to form and harden like a husk.

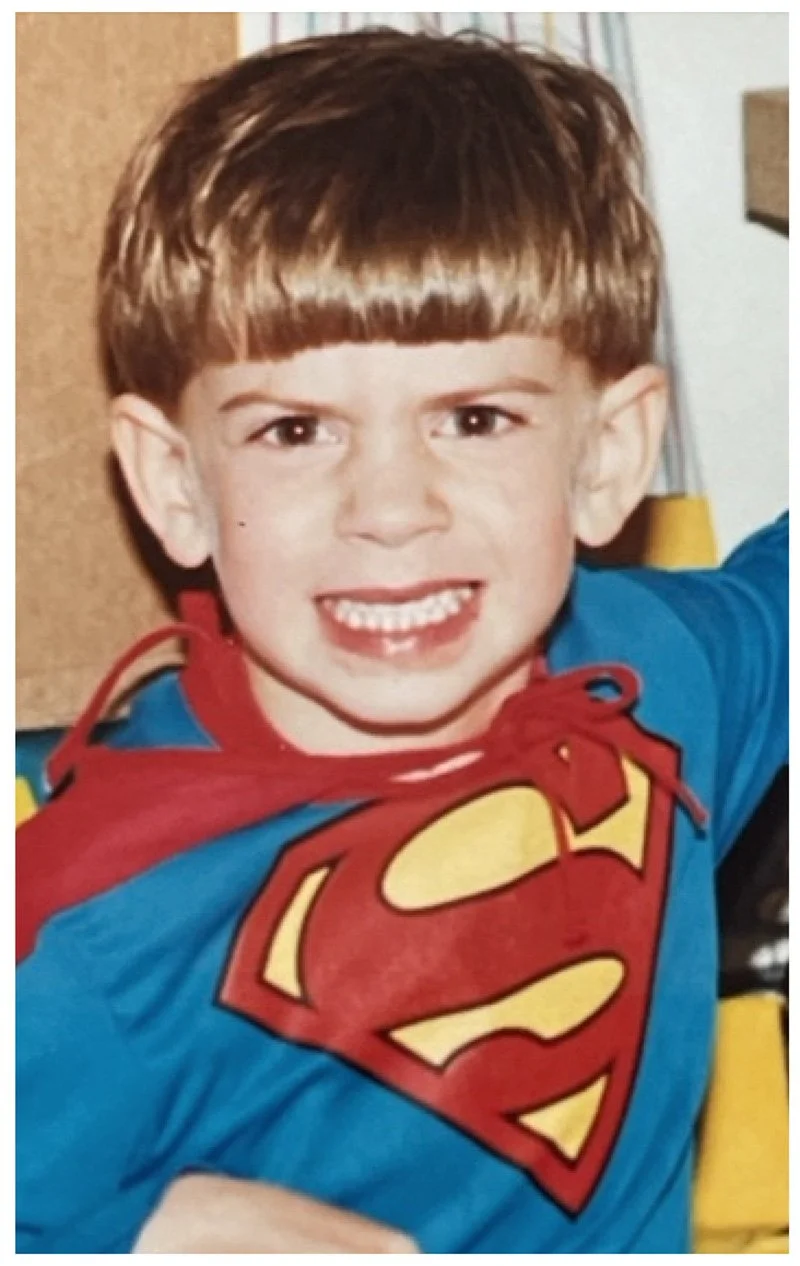

Undeterred, we reached for the stars. With a variety of disguises, he became any and every super hero (except The Hulk). Batman was very effective, complete with a mask (which was worn to tatters, requiring a hand-made replacement every other week). Superman was the go-to character though. For months and months and months.

When all else failed, he slung on his red cape and changed from a mild-mannered boy to the manly vanquisher of bad guys and mean weaklings — and any sorry fate visited upon his mother.

I loved each of these boys, each so different from the other, but each a way to empower a 5- year-old in the scary world, and each a way for a little boy to begin to feel his body and spirit, and yes, his masculinity. Just as he transformed a garlic press into a truck when he was 9 months old, he transformed these disguises with a shocking ease, without antecedent, into his developing self. We do that, don’t we?

The end (so far) of the story is simple. I managed to fund my later years on my own. And he became a doctor: Robin Hood, Superman and happily, not a tycoon.

“Big Head” Lawrence Bush

“When I Go” (Song) Lawrence Bush

Dana Jacobs

Judith Sokoloff

CAPITALISM SONNET

Sparrow

So long as I have to exist within

Capitalism, I should be able

To find joy in the things that I must do

To survive. Don’t let money frighten you.

It’s just a tiny piece of God disguised

As paper. It’s not evil, or a sin.

Money can liberate, if you are wise.

Play tricks with it. Give some to warriors,

Some to cobblers. Gamble a little. Nurse

The sick. Invest in silence. Play songs to

Grapevines; then harvest the grapes and make wine.

Be grateful, and await gratitude. You

Are wearing shoes the cobbler repaired.

Invite all to your table. God must be shared.

[The first sentence is taken from an interview with Sesali Bowen in Brooklyn Magazine, Winter/Spring 2022.]

100 WORDS

Wendy Saul

Around the table we six, short-term housemates who taught courses at the University of Pristina that summer, shared beers and stories.

A Kosovar native with a medical degree from Yale, told how he remotely guided local healthcare workers as they patched together the wounded.

“What do you do?” the doctor then asked, leaning back on his chair, puffing his cigarette and looking straight at my co-instructor.

“A poet” Robin replied.

”So interesting” the surgeon continued. “Though I work as a physician, I too am a poet.”

“Amazing” replied Robin, brightly. “Though I am paid as a poet, at night I still practice surgery.”

“Euphony” Bea Elderbee

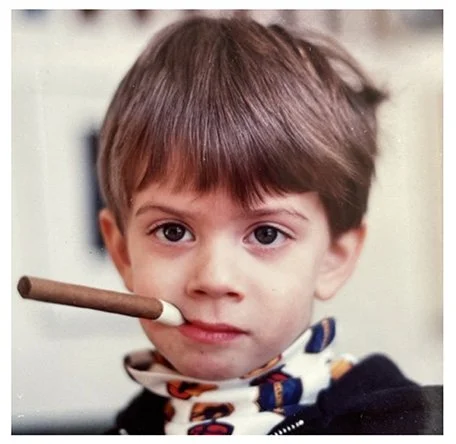

MY SON THE . . .

Christine Herbes Sommers

Children fully embody their disguises, not merely wearing them or using them to hide from or fool onlookers, but unself-consciously imbibing their character and subtly absorbing them into their own evolving foorms. This, I thought, would become useful to me if I could recruit my son into the effort of funding my older years. Over the years, he seemed to be more than willing, though not quite understanding it would inure to his benefit later.

I first thought — raise my child to be a tycoon! I was, after all, worried about money. If he made plenty (since I wasn’t and would likely never), that worry would disappear. All he needed was one prop to become a Wolf of Wall Street.

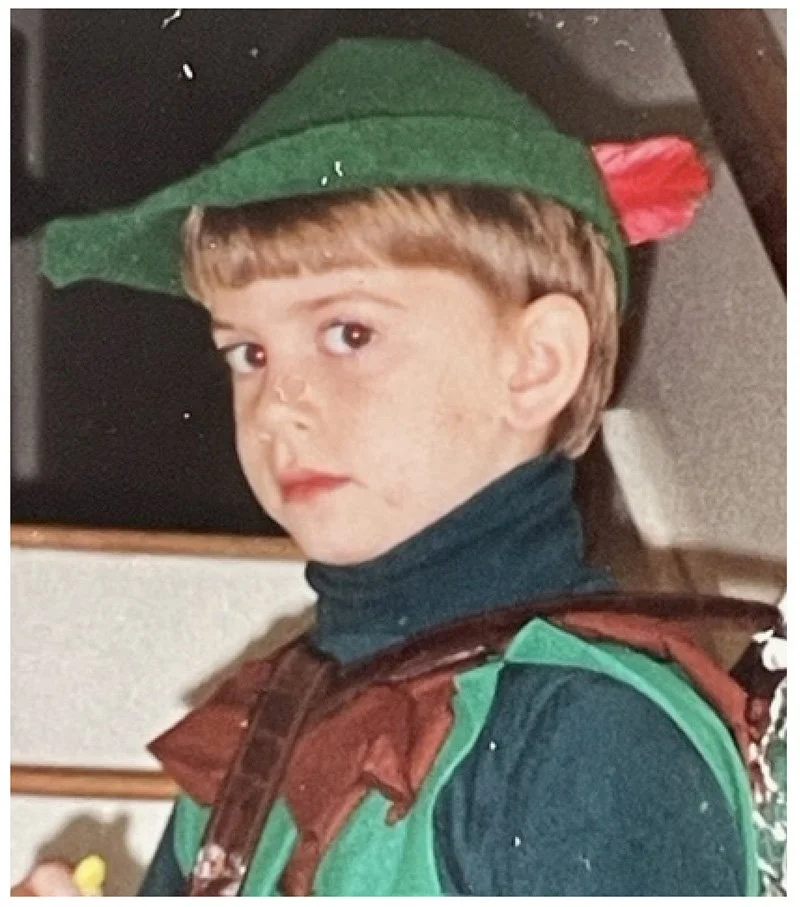

For some time, he wedged his cigar convincingly between his two fingers and adopted a sneer when he pretended to fire people. But this disguise was too mean for his basic nature. Also it simply wasn’t swashbuckling enough, nor did it have enough social conscience to be acceptable long-term to his mother. Which wasn’t the case with his next identity. Yes, he would rob from the rich and give to his dear mother in her dotage.

His absorption into this character was complete. He slept with his bow and arrow, and brandished it in the school library, on street corners, at the park. He rivaled Marx in his contempt for rich people. Sadly his ill-gotten gains never exceeded his Halloween haul.

From "Class of 1953B"

AUGUST 21, 1951

Ruth Wire

Surgery days are crazy. We students have to take vital signs of all post-op patients straight down from the OR. We race from room to room, checking bandages, blood pressure, temperature, and rate of breathing. There’s talk of starting a Recovery Room for immediate post-ops, but that will be in the future. Today I had all the patients on one side of the hall (the even numbers) and Louise had the other side, (the odd numbers). That’s eight patients each. I found Louise had gotten there before me and was arguing with the head nurse. The phone rang, and the head nurse talked into it, but Louise didn’t let up with her demands. When Louise saw me, she gave up on the head nurse. She took me aside and whispered, “Will you take 323 and I’ll take one of yours, like 324?”

I was immediately wary. Why did she want to swap? We’d never had a lecture on this in ethics. I didn’t know what to say. I felt vaguely uneasy. I asked her why she wanted to do this.

She became impatient with me, but refused to tell. Time was wasting, and I just wanted to get rid of Louise so I said okay. I tore down the hallway, checking the patients, and when I entered room 323, I was nervous. Here’s what happened next: Between two sandbags, his head immobilized, I saw a wizened man with a surgical patch over one eye. A cataract operation. He called, “Who’s there?”

I said, “It’s just your nurse. I’ll be checking your bandage. No, don’t move your head. Lie very still. You don’t want to disturb the healing process.”

He grunted. “You’re not my nurse. Where’s the other nurse?”

“You mean Miss Gross? She’s been reassigned,” I said.

“Good,” he said. “I can’t stand her. She’s a cold fish. She made me answer a lot of personal questions yesterday.”

“She had to take your history,” I said.

“What kind of name is Gross anyway? Is she a Jew? What is she doing in this hospital? The Jews should have their own hospitals!” he said, like a snapping turtle.”

Even though I was in a hurry to get to all my other patients, I paused. This man was one of those creatures with the leathery neck of a hard-shell albino reptile. I’d heard of them, but I’d never encountered an antisemite before. I was almost paralyzed. My heart beat fast. I knew now why Louise refused to care for him. I felt unequal to the job myself and sore at her. That rotten Louise! Of course she didn’t need to be Jewish for him to object to her. He was probably the surly type, and it sure didn’t help that Louise was naturally nasty. They hadn’t covered this in ethics.

I realized my name would reveal me, so I took his vitals on his non-seeing side, meanwhile wondering what to do about his prejudice. Nobody could like Louise, but in this way, she and I were linked. I could say nothing, but beneath my blonde hair and every-girl face, a Jew cringed. Then I felt the weight of my slaughtered aunts, uncles, and cousins, and my father crying, “They’re killing us!”

The man turned his head to look at my name tag.

“Keep your head still!” I said, and with my two hands cupping his ears, I held his head firmly, and he couldn’t move. “I am also Jewish,” I said, right into his face, “and there are lots of us at this hospital, and there are also negro girls in training here.”

His white skin turned red with embarrassment. He tried to turn away, but I wouldn’t let him move his head. “If you move your head you’ll ruin the surgery.”

He tried to say something, but by then, I was leaving the room. Again, I told him not to move his head. Outside the door, I began to breathe slow deep breaths. I felt wonderful. I felt like a Sabra in newly born Israel, proud. I even thought of sour, mean Louise, and her right to be who she is.

Matthew Septimus

FOUR SHORT PIECES FOR A THURSDAY AFTERNOON

Judith Dorian

just outside my range of vision

a presence holds me back

throttles certainty with doubts

gets stuck in my throat

like the wish bone that choked me

yet didn’t grant my wish

clever and fast-moving I steal my shadow which,

angered by the trick

leaps up onto the ledge and meows

•

there is something—

neither snail nor rodent, snake nor salamander—

that should leave its habitat

why? you ask

why not?

I coax it, plead, threaten it

to no avail

it shrinks back, darts glances this way and that

shunts from one rotten log to another

and sinks down onto the overgrown forest floor

high up in the Sitka Spruce

above the decay

a Spotted Owl hoots

•

last week I dreamt a melody

whose gorgeous shapes and colors

made the angels whoop

in the morning I only could recall threads of it

and so the next night I slept with one eye open

when the song again appeared in my dream

I leaped out of bed, scooped up the notes

tucked them into my piano

shut the lid for safekeeping

and returned to bed

while I slept, the notes flatted themselves

and seeped out from beneath the top

two or three stragglers stayed behind

•

I bought two shares of a goat today

a nanny goat

who had strict orders

to supply milk to a family in Malawi

some of which will become yogurt and cheese

and her manure will fertilize their garden

it seems to me that’s asking a lot of a goat

I don’t know exactly which part I bought—

the legs, udders, eyes, or hind quarters—

moreover, how many shares does a goat have

and what will become of the rest?

I wonder: can I buy two shares

of a man the same way—

not for milk, of course—

but for love? And which two shares?

His arms, brain, or other body parts?

the bank refused payment over the phone

and so I had to walk there

and argue with the manager

which cost me five shares

of time and three of frustration.

REMEMBER

Sparrow

Without

racism

Trump

is just

a fourth-

rate

standup

comic.

Judith Sokoloff

“Party People” Lawrence Bush

SHADOW

Rachel Berghash

I want to live like a shadow

be a shadow of a tree

I want to walk

in dark back streets

stand under a canopy

of the Grand Mosque

in Mecca

or sight the long Antarctic

shadow over the sea ice

much light

breaks my heart

the shadow of a lamp

beside me

is sufficient

if I am shunned

remember to give me a shadow

wrapped in silvery paper

or entrust me with the spirit of shadows

the night and nothing

Claire Marcus

From “MY STUFF, VOLS. 1, 2, & 3”

Mikhail Horowitz

One of the favorite pranks of my wild and misspent youth involved tearing off the barcodes from glass jars, tin cans and plastic containers and gluing them onto rocks. These scanner-friendly stones I would subsequently place on shelves, or hide among produce, in the local Grand Union supermarket. Shoppers were still finding the rocks more than a year after I had secreted them; some guy even tried to pay for one.

Judith Sokoloff

HAWK

Rachel Berghash

For Marty

A usual casual morning

until I walk into the bedroom —

perched on the window sill

a brown-white bird stares inside

with a stubborn look. I am stunned

by the size of the bird, a red-tailed hawk

I later discover, and think of your

sudden death the week before,

I imagine your slow ponderous

soul, now ephemeral, leaving your body,

traverses deserts and grasslands

before it finds a resting place

in this ominous lusterless bird

with a hook-shaped bill so dreadful, it fills

the room with a male aura, bidding me farewell.

FOOLING AROUND

Helen Engelhardt

I always was a fool for love

in my cap and bells

juggling desire and denial

on the outskirts of paradise

in my cap and bells

a motley clown

on the outskirts of paradise

making a fool of myself

A motley clown

a confessional jester

making a fool of myself

playing for time

A confessional jester

juggling desire and denial

playing for time

I always was a fool for love

PRE-USED

Esther Cohen

And now at this point

insane moment

of age and longing

cusp and pinnacle

my arms are different arms

my dreams are always

interrupted

longing becomes more

I can no longer do

This or That

As much as I still want

Wake up wondering

How I no longer care

about why

when a day

is not just a day

but right now