ON LEARNING LATE IN LIFE

THAT THE SHEMA IS A HAIKU

by Jessica de Koninck

Listen up people

we may not understand but

the whole project works

*

Often before lunch

I’ll look up from my laptop

stare out the window

*

In the center of

multiple universes

outside is inside

*

That sole apple tree

contains as much wisdom as

anyone can lift

*

Inexplicable

Multijurisdictional

Collaboration

*

Not a goose in sight

Where are all the birds today

Oh, now I hear them

*

I’ll tell you something

the source is all around us

everywhere we look

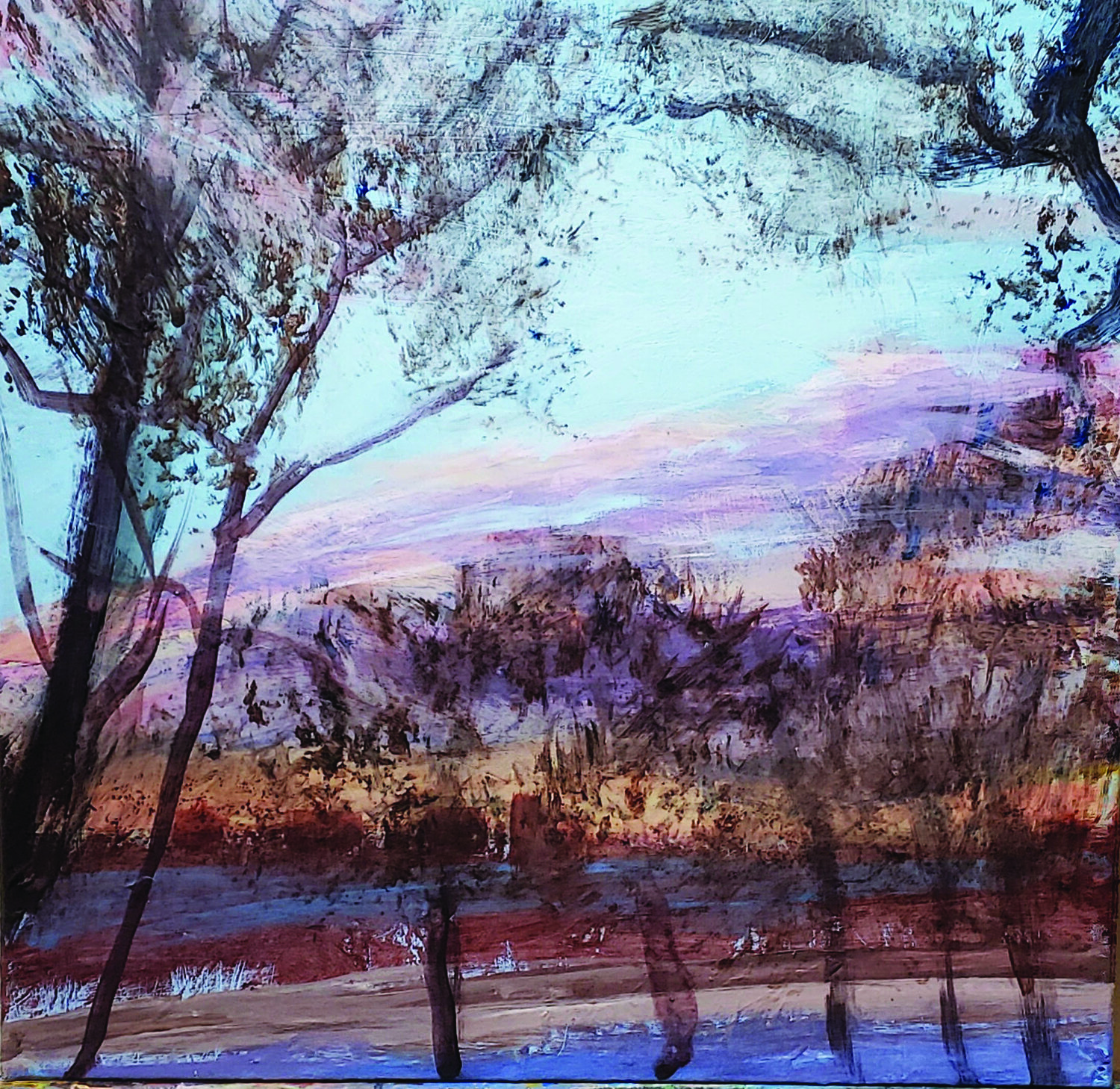

Doug Eisman

AFTER THE LONG WINTER

by Elaine Koplow

spring blusters forth like a wildflower

salesman peddling his wares from door

to door — stopping at every meadow

and lawn up and down the road.

Every year the return. Yet every year

a surprise.

Vibrant yellow along the fence —

the revenge of the forsythia I cut back

last fall. The hyacinths have unfolded

into purples and pinks, and crocuses

are jostling with daffodils in the breeze.

Shrubs long naked have put their clothes on —

all green and red and white. No longer

dormant.

And we are like the bare-branched

trees — storm-tossed but not broken —

ready to shed our winter skins, the need

for renewal reaching far deeper

than the roots of the perennials.

If only it were so easy

for us — to put our feet into the soil

and let the sun bring us to life.

“Postage Due” by Marc Shanker

Alte #11: OPEN CALL

100 WORDS

by Lawrence Bush

STOP! STOP! STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP! STOP. STOP. STOP! STOP! STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP! STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP! STOP! STOP! STOP! STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP! STOP. STOP. STOP! STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP! STOP! STOP! STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP! STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP! STOP! STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP. STOP! STOP. STOP. STOP!

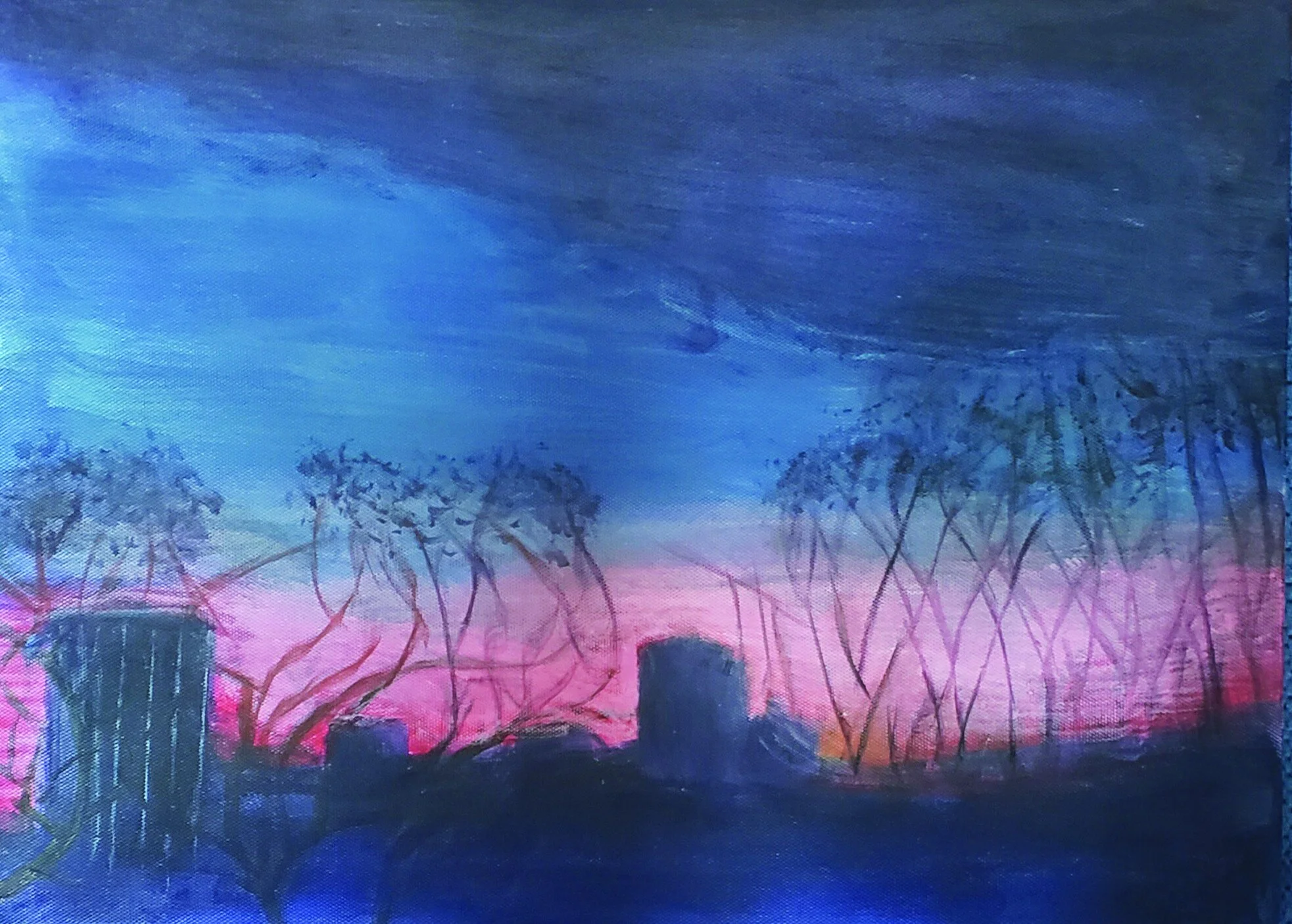

“Amber” by Dana Jacobs

RESOLUTIONS

by Barry Savits

I resolve to cry less,

weighing myself down

among the throngs of my fellow travelers

and feeling guilty.

It seems their needs are so great

that I cannot easily solve them,

sometimes not even one at a time.

So . . .

I resolve to exercise a more personal path

To be more out of the home active.

To increase my scope.

To making telephone calls,

communicating more

with my family and friends.

I want to realistically continue

my new found journeys in person,

though only if nature is willing.

Why not wish upon the stars.

They shimmer above for us

to see and enjoy their light.

Why not resolve to include them

in my embracing arms.

Maybe they will blink

in appreciation.

I’M GETTING OLDER

by Esther Cohen

Some years ago I said to an agent

before I actually was

This Much Older

I wanted to write a book titled

I’m Getting Older.

She said No One Wants to Hear That

and when I asked Why Not she said

It’s Just a Fact

and although I didn’t believe her

I didn’t write the book.

Even older today I wonder

what I would say now.

I wouldn’t talk about body parts

no organ recitals

wouldn’describe gastroenterologists

or even my favorite doctor endocrinologist

with the unlikely name of Clifton Jackness

mildly religious Jew I would

probably tell the story of a woman

named Naomi I met on the bus

just a week ago.

Naomi had a walker and large

vintage earrings. Can we talk

about our sex lives asked Naomi,

a total stranger who described herself as

a political activist. Presuming you have one

she added. Yes I do I replied.

So do I said Naomi.

And we both laughed.

“Demon Lover” by Lawrence Bush

WHAT DO WE KNOW

by Steven J. Gold

The vast depository

Of collected human knowledge and wisdom

Comes crashing down

In a pile of meaningless rubble

When confronted with

The presence

Of a tree’s green leaves

Shimmering in a breeze of

Golden light

Green leaves

Shimmering in golden light

WHAT I WANT TO BE WHEN I GROW UP

by Roni Fuller

“It’s not what you are, it’s what you don’t

become that hurts.”

— Oscar Levant (age, irrelevant)

“What a mess I’ve made of my life,

but oh, what a life I’ve made of my mess.”

—Roni Fuller (age, 30)

1958—Great dreams,

traveling to see the world,

make a name for myself,

show them all I can be the best,

damn the nay-sayers,

I will be there, profound, famous.

1968—So much has gone wrong,

college career dismal so far,

dead-end jobs, the dreams paled,

a disastrous, illegal war,

political turmoil, Capitalist greed,

the future looking grim.

1978—I guess I grew up,

at least a little bit.

Wife, child, a real profession—

HOUSEHUSBAND!

Writing like mad,

not yet ready to say “poet,”

but forty years old,

happy to be here.

1988—Still househusband,

becoming a poet,

thinking there is a novel in me,

three children, same wife,

settled, but more radicalized,

growing crops, cutting wood,

making a life unimagined in my past,

a pillar at Temple Beth-El,

Chair of Central America Task Force,

New Jewish Agenda.

1998—A year in Israel gone by,

children both struggling and thriving.

A poet: yes.

A novelist: no.

A crisis: wife has cancer.

2008—Wife is dead,

Two grandchildren now in my life,

Three books published,

and writing, writing, writing.

Age is not as hard as it might be,

and I walk, have friends,

my children are good to me.

What next in this crazy world?

2018—Another book, a publisher,

something more than a wish,

someone unknown likes my poems.

2022—Looking back, three long sequences,

each life-changing in many ways:

fifteen months on the Navajo Nation,

one year on Kibbutz Hanaton in Israel,

ten months in El Salvador.

An amazing life I had, am having,

a perfect wife, lost too soon,

exciting and interesting children,

wonderful grandchildren (now five),

and there is the future —

perhaps I’ll find out

what I want to be when I grow up.

“The Journey” by Marc Shanker

A PHONE CALL FROM SEYMOUR

by David Koulack

“Hi David,” he said, “it’s Seymour.”

“Hi Seymour,” I practically shouted. I was delighted to hear from him. We go back a long way — to 1968, when we were hired by Alf Shepard to teach at the University of Manitoba. It was quite a coincidence. Both of us Jews from the Bronx, the first Jews, as it turned out, to teach in the psychology department.

Memories came flooding back as we talked, and Seymour’s New York accent, much more profound than mine, permeated the conversation. We reminisced — there were so many fun and crazy things we had done together.

“Do you remember that poker game?” I asked.

“You mean the one when Al left the game early in a huff, stuffed his feet into Ed’s shoes that were a size too small and wore them for a week complaining all the time that his feet were sore?’

“Yeah, that’s the one.”

“And what about that ice fishing gig?” Seymour asked.

How could I forget it? There were six of us, all novices, at the ice fishing game. Someone had rented an auger, and I think it was Gerry Erickson who’d borrowed two tip-up poles that raised a flag when there was a bite. Seymour, who didn’t drink, drove us to Netley Marsh in his van, and after we drilled a hole in the ice and set up the rods, we retired to the van to play cards, all except Gatley that is. He got drunk and ran around the ice, bothering the few people who were there.

“You guys charged me with keeping him safe,” I said accusingly to Seymour. “I had to keep pulling down the flaps on his hat so his ears wouldn’t freeze.”

Seymour laughed at the recollection. “Yeah and remember how many fish we ended up catching? Good thing our wives went out and bought fish and had a bouillabaisse ready and waiting when we got home.”

“Hey, and what about those squirrels you harbored?” I asked, referring to the several occasions that I’d had to drive Seymour to a garage on McPhillips to pick up his car after it had been rid of a family of squirrels that had used its engine for a home during the winter.

But the truth was, those days were long gone. Reminiscences were all they were. Instead, Seymour and I had settled into a more or less steady routine. We’d go out for lunch on occasion. We’d call each other up when it was time. We lived a few blocks from each other, so I’d drive over to his house and wait while Seymour made his way along the walkway of his house to the car. Then I’d get out and hold the door open and help him into his seat.

Seymour knew all the restaurants in town so he’d get to choose where we’d go and he’d generally order for both of us. We’d sit and talk and laugh. Often the people at the restaurant would recognize Seymour and drop by our table to ask him how he was doing and chat for a bit.

But then Seymour moved into a condo and I moved across the river, and our lunch time meetings became less frequent. We didn’t exactly lose touch, but we just weren’t as prominent in each other’s lives as we had been before. And here, out of the blue, he’d called and we were reminiscing and laughing together, and I remembered how much I missed him. Maybe we’d go for another meal, I thought. Then Seymour told me why he had called. “I’m calling to say good-bye.”

I wasn’t sure what he meant.

“This afternoon I’m going to have myself killed,” he said. “I meet all the requirements. My cancer is in its terminal stages and I’ve got all my marbles. It’s one of the good things about Manitoba. Assisted dying is a right, and I intend to exercise that right this afternoon.

“I just turned 87 yesterday and I think that’s enough. I’ve organized everything. My ashes will be scattered in the Lake of the Woods, except for a smidgen which will be scattered at the 174th Street Station in the Bronx.

“So anyway, I’m just calling up to say goodbye. I don’t believe there’ll be anything going on for me when this is over, but if there is, I’ll be sure to let you know.”

“Houdini like?” I asked.

“Yes,” Seymour answered, and we both chuckled before he hung up.

“Pandemic Goodbye” by Jeff Blum

HERE AND THERE

by Rochelle Shicoff

Here — Predictable tippling of chartreuse leaves

surrounded by screens of yellow chrome forsythia.

There — Skeleton trees smoked into burnt umber.

Here — Pink, orange, red tulips boated from Holland.

There — Cement into fine dust, twisted metal.

Here — Blossoms light the sky in straight,

40 foot white-to-be ornamental pears and apples.

There — Only black plastic, miles of body bags.

Workers gather, gather out of graves the plastic,

delivered to families holding shovels.

Here — Spring ground breaks for life.

There — Spring breaks the ground to receive

memories.

WHAT WE REMEMBER

by Norma Bernstock

Now when my father can’t even recall his wife’s name,

he still remembers that salami is his favorite food.

I see us all at Rockaway Beach,

the stained paisley quilt squeezed between

rented umbrellas and striped canvas chairs,

Beach 35th Street, close to the knish and hot dog stand

though we never bought a thing to eat.

Mostly it’s the scent of salami

and fresh seeded rolls that stays,

sandwiches thrown together early on a Sunday morning

when Dad awoke to a sultry sun and declared it a beach day!

Although Mom complained there was nothing for lunch,

we always had a Hebrew National salami in the fridge.

At times like this, Dad would volunteer

to pick up rolls at the bakery

while Mom scurried around the house

in search of the plaid, insulated beach bag

and the blue Coleman jug to be filled with Kool Aid

or some other sweet concoction,

and always a bag of over-ripe peaches and plums for dessert,

and the ride home in the car, salt-water hair

pasted back by the breeze,

damp swimsuits with sand digging into skin,

unable to breath deep from the salt in our lungs,

not knowing then that the taste and smell

of salami and rolls with seeds

would outlast the memories of a fifty year marriage.

NIGH NIGHT

by Rozann Kraus

Life is like

that

one letter altered

alerting not

none is changed

charged with meaning

leaning in ways

to sway

so close to being closeted

slow to understand

standing under the weight

of waiting

confessing confusion

the mirror miraculously

shows him young

ageless and agile

yet he is not.

As life

is like that

moving clockwise

wisely

RECEDING

by Ruth Wire

At ninety-three, my mentally intact mother

slowly loosens her hold on life.

Shoulder arthritis’ painful injustice

she treats with an onion poultice.

The doctor reports her body’s making

less than half the needed red blood cells;

nodding, pale, she jokes, “I can’t live forever.”

A faulty heart valve

that’s been a murmur all her life

now refuses to deliver all the blood

passing through its partly closed lips.

My mother shrugs and tells the doctor

she cooks good clam chowder,

and just taste the shrimp cocktails

for family dinners.

Immersed in red sauce,

it’s plump and pinker than she is.

She still lives in her mobile home

with flowers, trees, and a cat.

She waters the place from her walker,

but has energy for only one hour

before she needs two hours of rest.

We shop each week for grape juice, liver, and Green Magma.

Lately she’s been absent at Little League games,

music concerts, movies, and plays.

A library volunteer delivers books five-at-a-time.

She craves new things:

the energy to take a shower, to mop a floor,

to walk to the store.

She goes back and forth to the mailbox.

We visit the undertaker.

I cry softly while she plans her funeral.

Everything is paid for.

She lectures me on what to do with money

knowing I’ve never had much.

I think she’s taking this too calmly.

I ask, “Where’s your anger?”

“Listen,” she says, “I’m too busy enjoying my petunias

and the sun to be mad about anything.”

I hold her close.

She’s become so small and wrinkled,

also a little remote,

like someone fading in a silent film.

The other day she doesn’t answer the phone,

so I run over to find her on the porch

gazing at the potted geraniums.

“It’s such a nice day. Smell the air,” she says.

It’s sharp with cut-grass and

puffed with sweet alyssum.

“I feel dizzy,” she says, trying to rise.

Suddenly her head droops

and her voice comes from the dim world

that’s pulling her.

“Wha—Wha—na--ga.”

I call 911, but cancel the call

when she awakes by herself.

“It’s time for a little rest,” she says.

“The air makes me sleepy.”

But I know she visited her next home

to see if the plumbing is okay

before she moves there.

“Last Light on the Hudson” by Jeff Blum

REMEMBERING

by Shirley Adelman

The last branch has fallen

with the death XXXXXX of Ed Itzenson

who remembered the day

I was born.

Ed was one of the boys sitting

around our livingroom, noshing

fruits and sweets my mother

served, kibitzing with my brother

and their friends.

The boys’ voices drifting into

my room, lulling me to sleep.

Their laughter jarring me awake.

A late in life child: now

alone with memories.

HANGING LOOSE

by Mary K. Lindberg

No more mountains,

just small hills, fancy street

bumps. Skin, like breath,

begins to flag, hang loose.

Exploring reveals fault zones

and hairy surprises rising,

startled from a deep sleep

near spawns of speckled dermis.

Not a sudden landslide

bringing down homes,

nor a tornado whirling

skinny debris —

more like a glacier,

thinner skin exposing

twisted purple and blue

rivulets, adipose deposits

swaying in spite of

inner denial.

This is what sixty

looks like.